Lebanese Mini-Bus

This morning, my Turkish friend Ozge (she’s in my Arabic class at ALPS) and I decided to meet up for a quick coffee before hopping on a mini-bus to the town of Zahlé in the Bekaa Valley. Mini-buses aren’t actually buses, but rather, large, white mini-vans. If you get on the bus at a transport hub, like we did, the driver will wait until the van is full before leaving – otherwise, you’ll make random stops along the way to pick up additional passengers. Once the bus is filled, there’s not really a set route per-say. Instead, there is generally defined final destination and as long as you want to go somewhere that’s more or less on the way to that final destination, the driver will drop you there.

The drive up to Zahlé cost us 4000 Lira (about $2.50) each and took about an hour and a half. Driving rules and regulations don’t really seem to apply and the bus can get pretty cramped and sweaty, but luckily I got a seat near the window – yesss! Fresh air! Aside from the frequent swerves and break-slamming (I tried to take comfort in the fact that none of the other passengers seemed nervous), the ride up was really pleasant. The driver blasted Arabic music which set a fun mood as we drove up through the mountains and villages east of Beirut and into the Bekaa Valley.

View on the drive to the Bekaa Valley

The Bekaa Valley isn’t actually a valley, which is kind of weird. It’s actually a plateau between two mountain ranges in Lebanon. The plateau is this huge agricultural region here in Lebanon – it used to be one the ‘bread baskets’ of Rome. Today it’s still one of Lebanon’s most important farming regions, and is famous for the delicious, locally produced wine.

The Bekaa Valley isn’t actually a valley, which is kind of weird. It’s actually a plateau between two mountain ranges in Lebanon. The plateau is this huge agricultural region here in Lebanon – it used to be one the ‘bread baskets’ of Rome. Today it’s still one of Lebanon’s most important farming regions, and is famous for the delicious, locally produced wine.

There’s actually also a long history of cannabis production in Bekaa, and the sale of ‘Red Leb’ (nickname for the high quality pot produced there), has long provided a major source of income for producers living in the valley. The production is nowhere near as prolific as it once was, but nevertheless, the region has maintained its notorious reputation. Woot.

The bus dropped Ozge and I in the center of Zahlé around 1pm. Okay, not going to lie, it wasn’t exactly what we had expected. Lonely Planet writes:

“Known locally as Arousat al-Beqa’a (Bride of the Bekaa), [Zahlé] is set along the steep banks of the Birdawni River (locally known as ‘Bardouni’), which tumbles through a gorge, cutting a burbling channel through the centre of town.”

The Birdawni "river" of Zahlé

So, we get off the bus expecting to see this beautiful village with a huge river running through it’s center. What we saw initially was more of a dusty intersection with no river in sight. Whatever, we’re up for anything, so we started wandering down the main city road and off to our left we noticed this little babbling stream, about an inch, maybe an inch and half deep…the roaring Birdawni. Nice.

But, I have to say, Zahlé itself turned out to be a charming city after all, sprinkled with Ottoman era houses (that somehow survived the civil war – which destroyed most of the city), mixed in with more modern Lebanese architecture. It’s definitely not a must see on a tourist agenda, but apparently it acts more as a stop over town for visitors traveling through the Bekaa Valley or as a base for those who wish to spend a few days in the region, hopping back and forth from Zahlé, to nearby cities.

It’s a primarily Christian city, so most stuff was closed, given that it’s Sunday. But still, we had a really nice walk down the main street, Rue Brazil – named for the huge number of the town’s population that migrated to Brazil around the time of the 1860 massacre (communal fighting between Druze and Christians). The Zahlé Lebanese living in Brazil sent back money to their families still living in Lebanon and apparently that money really helped the town get back on its feet after the massacre – and so they named the main street after Brazil.

Random fact: Today, the greatest population of Lebanese outside of Lebanon is in Brazil. Who knew??? I want to go to Brazil!

Downtown Zahlé

Hungry, we decided to break for lunch. Lonely Planet told us that the Zahlé is actually famous for its riverside, open-air cafés. Fantastic! Once our bellies started rumbling, we stopped at the first place we saw, the Grand Hotel Kadri, where we enjoyed a delicious mezze, washed down with ice-cold Almazas. The hotel is beautiful, and actually served as an Ottoman hospital during World War I and was later home to the chief of the French Army during the French Mandate of Lebanon.

Ozge! Eating our mezze at the Grand Hotel Kadri

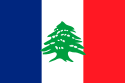

Lebanese Flag under the French Mandate

Quick history behind the French Mandate in Lebanon ;): So after World War I, in 1920, the Ottoman Empire is divvied up between the French and the British in the Treaty of Sèvres. The British get Palestine and Iraq (both of which they proceeded to seriously fuck over), and the French get Greater Syria which = modern day Syria + Lebanon. So that’s the beginning of the French Mandate. The French then separate Syria and Lebanon and Lebanon gets this funky new flag that’s a combo of the French and Lebanese flags. Anyway, I won’t go through the whole history of the French presence in Lebanon, but the country gets its independence in 1943 and the French finally leave in 1945. Oh yeah, you know you were dying to know all that info.

So anyway, after lunch, we caught a ‘service’ (fixed price taxi) to the Château Ksara, the oldest winery in Lebanon. ‘Ksar’ means fortress in Arabic, and the current winery stands over the site of a medieval Roman fortress, and the caves where the wine is now made were once the cellars of that original Roman fortress. So now, flash forward to the mid-1800s – the Roman fortress is long gone, but the caves are still there, unbeknownst to the locals living in the village. Jesuit priests build a monastery over the caves and one day, a priest, chasing a fox that was threatening his chickens, discovers the caves beneath the monastery. He tells his fellow Jesuit priest buddies and they think ‘Score! Perfect place to store some alcohol!’ And so the winery is born in 1857 CE. The soil and weather in Ksara was perfect for growing grapes – vines were grown along with aniseed (a flowering plant that tastes like black licorice), to make Arak, and business started to boom for the Jesuit priests of Ksara. In 1972, the priests sold the land to several Lebanese families who further expanded the business…and that catches us up to today!

Château Ksara

One thing about the Château Ksara that’s particularly fantastic is that you can take tours of the winery for FREE, complete with a complimentary wine tasting at the tour’s finish. YUM. Our guide took us through the chilly 2km of caves beneath the winery where the wine is stored in oak barrels and bottled wines are held until they’re ready to sell. The Arak is actually produced in a separate facility, above the caves, but the smell of the aniseed seeps down into the caves, mixing with the smell of oak and wine. Mmmm boy!

Inside the caves of Château Ksara

Arak produced in Château Ksara, called Ksarak

Okay, so in case you don’t know, Arak is clear, aniseed-flavored alcoholic drink that’s very popular here in Lebanon. It’s actually a brandy, made from grape leaves, the skins and seeds of red grapes, and aniseed for flavor. It’s exactly the same as Greek ouzo, Turkish raki and Italian sambuca – everyone claims it as their own. The Lebanese side of my family drinks Arak regularly and as a child I actually thought that all alcohol smelled like black licorice. Oh yeah. I was a bright kid.

According to Lonely Planet, “Experts say the best way to tell the difference [between good and bad arak], is by how you feel when you wake up the next morning: the better you feel, the better the arak the night before.” I love it! To drink it you usually add water or ice, which turns the drink to a milky white color. Personally, I’m not the biggest fan of the taste, but it’s served so often, I’ve learned to stomach it.

After our free tour, Ozge and I decided it was time to head back to Beirut and headed out to the main road in Ksara to hail a minibus. There are no bus stops. You just stand on the side of the road and passing taxis and minibuses honk as they approach you. If you proceed to wave at them, they’ll slow down. You tell them your final destination and if they happen to be headed there or at the very least in that general direction, they’ll barter a price with you and you hop in, sliding the door shut as the minibus speeds off.

Inside the mini-bus on the drive back to Beirut

Our drive back to Beirut was an adventure. Crammed in the back between your fellow sweaty passengers, you all share communal water bottles provided by the driver, which you drink the ‘Arab way’. Drinking the ‘Arab way’ means that you don’t let the bottle touch your mouth – you tilt your head back and pour water into your mouth. They’re all pro at this, so no one seems to miss or splash whereas I, the foreign idiot, usually end up splashing water all over my face and clothes, especially on a bumpy bus. Damn. Ah well.

Stops were made at wells to refill the water bottles, at one point the driver made an ice-cream stop, passengers share cigarettes and snacks – it’s a really welcoming atmosphere but totally confusing and hilarious for a first-timer like me. Our driver was especially reckless and more than once I found myself with my eyes squeezed shut and my hands tightly gripping the seat. He nearly hit every single person we stopped to pick up, and one man almost fell over as he jumped to avoid being pummeled by the oncoming van. And the driver would just laugh this maniacal laugh. He was insane. No really, I think he was.

Somehow, we made it back to Beirut alive around 6:30pm. We parted ways and I headed home for a home cooked dinner with Stephen and Shadee, before heading back out to meet Ozge at Café Younes, where we studied Arabic until 11pm. A full Lebanese day. Not bad, huh?